Lawmakers don’t agree about how to use the money received by the state from the sale of Raleigh’s Dix hospital.

By Thomas Goldsmith

Reprinted from North Carolina Health News, originally published June 21, 2016

North Carolina legislators want to place 150 new behavioral-health beds in hospitals in rural areas of the state, using some of the proceeds of the sale of the Dorothea Dix campus.

The idea, contained in the budget proposal from the state House of Representatives, is getting kudos from some quarters as a way to increase scarce mental-health resources in rural counties.

But advocates for people with mental illness, as well as some health-care professionals, say the plan neglects significant parts of North Carolinians’ behavioral-health needs, namely, community treatment options.

“The Dorothea Dix money is really important to our members and our organization because Dorothea Dix had a legacy of being innovative in the treatment of people with mental illness,” said Nicholle Karim, public policy coordinator for the North Carolina chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“We are really glad the General Assembly is committed to trying to find a solution. We are also really committed to the idea that when people go to the hospital, they need a place to go after they get out.”

Adding beds

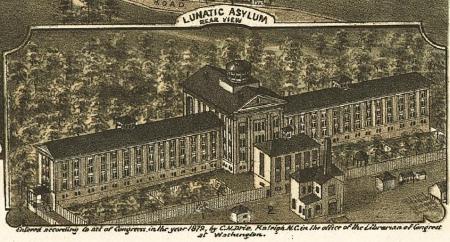

The city of Raleigh agreed to pay the state of North Carolina $52 million for 308 acres of land on the Dix campus in a deal that closed July 24, 2015. Pushed into existence by 19th century reformer Dorothea Dix, the hospital bearing her name sitting on the broad hillside east of downtown Raleigh served people with mental illness between 1856 and 2012.

A mental health reform effort started in the early 2000s lead to the closing of Dix and hundreds of other residential beds for people with mental illness, that in turn has led to shortages of care in rural parts of the state. At the same time, emergency departments in urban hospitals are seeing overflows of behavioral-health patients, who wait four days on average for a bed in an inpatient facility.

The House budget includes plan to add inpatient beds in rural areas, 50 each in rural counties in the state’s three regions, using some new beds and some conversions of existing acute-care beds.

“I want to compliment the General Assembly,” said Christine Craig, vice president of government affairs at WakeMed Health and Hospitals. “They are trying to come up with some creative solution and honor what the Dix money should be spent on. They looked across the state and looked at areas that have unused acute beds.”

The communities in rural areas, including one to be located near Wake County, should get both improved behavioral-health services and increased employment opportunities from the new beds, Craig said.

More than beds

The North Carolina Hospital Association backs the creation of beds in rural hospitals in principal, said Julie Henry, its vice president of communications.

“We’re supportive of the use of the Dix money for that purpose,” Henry said. “The devil’s in the detail. I think that the idea of making use of some of the beds that exist is appropriate.

“We know that just adding more beds is not the answer,” she said. “The biggest issue we face right now is boarding people with mental illness and substance abuse problems in our emergency departments.”

The Senate plan calls for spending less than half the House’s proposed $25 million, earmarking $12 million in funding to “rural areas of the State with the most limited inpatient behavioral health bed capacity in comparison to their needs.”

In addition, the Senate discusses putting Dix money not only toward psychiatric beds, but also for facility-based crisis centers, like the UNC-staffed WakeBrook center that Wake County funds in Raleigh. These centers care for people in crisis, sometimes negating the need for patients to go to a larger psychiatric hospital. But for the many patients who do need a bed, their options are limited by the shortage of residential beds.

“Our role there is to assess and determine next steps,” Denise Foreman, assistant to the Wake County manager, said of WakeBrook. “But everything is full; the state beds are full, the private beds are full.

“They are supposed to come and leave in 24 hours and they are stuck there for days. We have to close the doors for our assessment center and we have to start diverting people to a hospital.

“If you have a minor infraction, they have to take you to the jail.”

Dial up a doc

Help for people with mental-health crises in rural areas is also hard to find, leading to the House provision to locate the new beds at hospitals with telepsychiatry capabilities. Telepsychiatry allows patients in areas lacking enough clinicians to deal with a psychiatrist through a remote, secure video connection, with a health professional in the room with the patient.

Telepsychiatry has been widely adopted as a cost-saving measure and has a strong North Carolina center in East Carolina University’s Center for Telepsychiatry and E-Behavioral Health. The associated North Carolina Statewide Telepsychiatry Program provides connections to hospital emergency departments across the state.

Advocates and mental-health professionals have good things to say about telepsychiatry, but also wonder whether its use represents another attempt to address the issue in a piecemeal way.

“We know that telepsychiatry is an innovative way to provide psychiatric services to folks,” said Robin B. Huffman, executive director of the North Carolina Psychiatric Association. “We hope that when these beds are established there will be enough staff to treat these patients.”

Psychiatrists who treat patients via telemedicine should be familiar with the person’s community, so that he or she can make recommendations for local services, Huffman said.

The NC Psychiatric Association hasn’t taken a position on the House versus the Senate plans. In Wake County, the local branch of the National Alliance on Mental Illness says more money should go toward a wider range of care.

“We’ve always thought that [Dix] money was supposed to be earmarked for people who are out of hospitals,” said Gerry Akland, past president of the NAMI Wake County chapter.

“They really need strong support services. We’re strongly advocating for supported housing for people.”

People who qualify for Supplemental Security Income disability payments from Social Security often can’t afford a one-bedroom apartment in a low-income neighborhood, Akland said. But those who can find a place to live can live independently with the help of an ACT, or assertive community team, of mental health professionals, nurses and other specialists.

“If they could have an ACT team to come by once a day, that would certainly keep them out of the hospital,” Akland said.

But that’s only if someone has a place to call home.