To be announced!!

Stay tuned for details on this website.

To be announced!!

Stay tuned for details on this website.

You can tune into our presentations, which were recorded during our Lives on the Hill event on Oct. 16.

Mebane Rash: Putting Dorothea Dix Hospital into historical context

Fitzhugh Brundage: How communities remember

Jon Crispin: The Willard Suitcases: A creative memorial to patients of a psychiatric hospital

Oral Histories: Six people who were connected to Dorothea Dix Hospital recount their memories (excerpts)

Part of our work with Lives on the Hill has included recording the oral histories of people who were at Dorothea Dix Hospital, either as a patient, a health care provider, along with family members of patients and providers.

This video contains excerpts from interviews conducted between July-September, 2016.

Special thanks to Eloise Brinson, John Myrhe, John Felicione, Helen Huske, Margery Sved, Margaret Raynor

More than a hundred people gathered Sunday afternoon to reflect and discuss what should be part of a memorial to the now-shuttered mental health facility.

Dorothea Dix, the former state mental hospital in Raleigh, once formed a community where patients and professionals left the grounds together to attend plays at Memorial Auditorium, spend weekends at the beach, and go to football games at Carolina and Duke.

It was a place where one huge dining hall served meals and the other was used for bake sales, as a “treatment mall,” as well as talent shows with remarkable performances by patients.

And it was a treatment center where eight people sometimes were required to hold down an anesthetized patient during electroconvulsive shock therapy.

These memories of decades past, some chilling and some charming, emerged Sunday as scores of people with connections to Dorothea Dix Hospital began to lay plans for its remembrance.

Former patients, volunteers, professionals and historians, they gathered at N.C. State University’s Talley Student Union to take part in the North Carolina Health News project, Lives on the Hill. The ongoing effort seeks to spur discussion on how the hospital should be memorialized in the new park planned for more than 300 acres of the west Raleigh site.

Click here to see an interactive timeilne on the history of Dix hospital.

“Thanks to Dix, and thanks to all the processes I went through and the work that I did, I can talk to people, I have a voice,” former patient Eloise Brinson said in one of several videotaped oral histories presented Sunday.

The table for an afternoon of shared memories was set with presentations by:

• Mebane Rash, editor-in-chief at the nonprofit Education NC, who spoke on the history of Dorothea Dix and mental-health reform in North Carolina. “The lives lived on this hill can and should inform public policy in the 21st century,” Rash told the gathering.

• Fitzhugh Brundage, professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who used examples of the state’s war memorials to address the day’s central question: “How do we connect the past to the future?”

• Jon Crispin, the Massachusetts photographer who discussed and showed images from “The Willard Suitcases.” His project depicts belongings left behind by decades of residents at the Willard Asylum for the Chronic Insane in New York State.

“The connection between the staff and the patients were the main reason these cases weren’t thrown away,” Crispin said, noting that staff were too attached to the patients to throw away their belongings once they died. “In many cases, families declined to come and pick up the cases or pay for shipping.”

At Dix, those connected to the hospital said Sunday, the community worked together like family, sometimes literally and at other times figuratively. Generations of staff lived in houses on the grounds, and patients and professionals worked together for decades at times.

“It was teamwork and it was a big family,” said John Myhre, pharmacist at Dix from 1972 until 2009.

Myhre, who had been interviewed by NC Health News’ team of videographers, also attended Sunday’s event. Before the presentations, he said an account of Dix’s legacy should include the research carried out there on a variety of medications including lithium. Trials were performed by drug companies and included informed consent on the part of participants, he said.

Major changes in medication practice for people with mental illness also took place during the latter years of the 20th century.

“When I first started they were giving monster doses of thorazine,” a powerful antipsychotic drug, Myhre said. “A drugstore dose would be 25-50 milligrams four times a day. I saw lots of doses of 5,000 milligrams.”

The video interviews, portions of which were shown during Sunday’s event, gave a broad range of opinions and facts about what informants had experienced at the hospital.

Brinson, a former patient, recounted being disappointed when the hospital was closed.

“Dorothea Dix should have been developed as a community for the mentally ill,” she said. “People could have gone out into the community and worked and come home [to Dix].”

Margaret Raynor, a former psychiatric nurse at Dix, said during her employment, the state of North Carolina reversed direction on the hospital that had served so many people.

“I was crushed,” she said. “I will tell you that the person who was head of DHHS had come and told us they were going to build a new Dix.”

NC Health News staff and writers were on the grounds of the old Dorothea Dix Hospital in Raleigh Saturday, July 23, collecting stories of people who had connections to the institution.

The city of Raleigh sponsored an all-day event, Destination Dix, meant to get people out onto the property, which was acquired by the city from the state of North Carolina last year.

“The goal has always been to make Dix a world class destination park that all North Carolinians can be proud of and enjoy,” said Mayor Nancy McFarlane in a May press conference where she announced the event . “In addition to bringing the community to this beautiful location for a great event, Destination Dix will spur their imagination about what they want the park to be; the sky is the limit.”

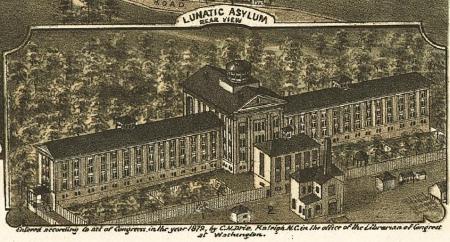

In 2010, despite the protestations of many in the mental health advocacy community, Raleigh’s Dorothea Dix Hospital shut its doors after being in continuous operation since 1856.

As the state constructed a new facility in Butner to replace Dix, those arguing for its closure said that the facility had become too antiquated, required too much upkeep and in some cases, had become too dangerous to continue treating patients there.

But many advocates argued that the institution, with its storied history, was an essential part of North Carolina’s mental health infrastructure, providing beds and a safe place for the state’s mentally ill.

Nonetheless, the institution on Raleigh’s Dix Hill closed and for the last five years, there’s been debate as to the future of the property. Last year, the General Assembly approved the $52 million dollar sale of the property after several years of negotiation.

Meanwhile, the living history of the hospital is slipping away as former workers, residents and patients move away or pass away.

Now, NC Health News is looking to gather stories of people who had connections to the place: whether as patient or members of their families, staff and their families, and children who grew up in the staff housing on the property.

Some people have multiple connections, like Ellen Beidler, who did a rotation at the hospital while training as a psychiatric nurse. Beidler said she also had a friend who was a frequent patient, had neighbors who had lived on the property and had friends who worked there.

Robin Madison who has lived in neighboring Boylan Heights for more than 20 years said she’d often encounter patients in her neighborhood.

“I remember… we were sitting out on the front lawn, in lawn chairs. We were having a drink in the yard on a beautiful spring day and someone coming up… and just talking to us, but obviously confused about where they were,” she said, adding that she and her friends would point those folks back to Dix. “That happened all the time.”

Madison also said she goes sledding on the property in the winter – in the days when the hospital was in operation, she and her friends would be “chased off,” but she said now no one chases them away.

Countless North Carolinians had small encounters at Dix, which served as a training location for generations of mental health professionals. One doesn’t have to talk to a North Carolina native for long to find a connection.

Chan Evans was a graduate student in teaching in 1992 when she taught classes to adolescents at the facility.

“They were the best students I ever had,” she said. “They were 4 to 6 students in a class… and I just remember their writing ability was just really excellent writers and I don’t know if that was another part of their therapy in another part of their day, but I was so impressed with them.”

All these people readily talk about their time at Dix. But one group of Dix alumni do not speak as readily about their time there – former patients.

Madison is also one of the many North Carolinians who had family members who were patients at Dix, but, as in so many families, the details were shrouded in stigma. Her grandmother and a great-grandmother were both were institutionalized at the hospital.

“I’m pretty sure that my mother didn’t know where her grandmother was. Nobody talked about it,” she said. Madison’s mother’s mother was a patient for a short time, but her Madison’s great-grandmother lived at Dix until she died.

“She and her sisters pieced it together,” Madison said. “They kind of guessed about it”

“With my grandmother, I think at one point she was diagnosed as schizophrenic. I’m not sure that was correct because that was a label back in the day and it was a catch-all,” she said, remembering her grandmother’s odd behavior at times.

Madison also said one of her aunts has “blocked it all out.”

We’re looking for the good and the bad, the triumphant and the troubling.

There are several ways you can participate:

♦ Check out our website: www.livesonthehill.org which will have new content soon.

♦ Call our reader story line to record a memory that’s less than 5 minutes long: (919) 659 LOTH/ (919) 659 5684

♦ Write us at: livesonthehill@gmail.com

♦ And keep your eye out for announcements about our event on Sunday, October 16, from 1-4:30 pm, at the Talley Student Center on the campus of NC State University.

Lawmakers don’t agree about how to use the money received by the state from the sale of Raleigh’s Dix hospital.

Reprinted from North Carolina Health News, originally published June 21, 2016

North Carolina legislators want to place 150 new behavioral-health beds in hospitals in rural areas of the state, using some of the proceeds of the sale of the Dorothea Dix campus.

The idea, contained in the budget proposal from the state House of Representatives, is getting kudos from some quarters as a way to increase scarce mental-health resources in rural counties.

But advocates for people with mental illness, as well as some health-care professionals, say the plan neglects significant parts of North Carolinians’ behavioral-health needs, namely, community treatment options.

“The Dorothea Dix money is really important to our members and our organization because Dorothea Dix had a legacy of being innovative in the treatment of people with mental illness,” said Nicholle Karim, public policy coordinator for the North Carolina chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“We are really glad the General Assembly is committed to trying to find a solution. We are also really committed to the idea that when people go to the hospital, they need a place to go after they get out.”

The city of Raleigh agreed to pay the state of North Carolina $52 million for 308 acres of land on the Dix campus in a deal that closed July 24, 2015. Pushed into existence by 19th century reformer Dorothea Dix, the hospital bearing her name sitting on the broad hillside east of downtown Raleigh served people with mental illness between 1856 and 2012.

A mental health reform effort started in the early 2000s lead to the closing of Dix and hundreds of other residential beds for people with mental illness, that in turn has led to shortages of care in rural parts of the state. At the same time, emergency departments in urban hospitals are seeing overflows of behavioral-health patients, who wait four days on average for a bed in an inpatient facility.

The House budget includes plan to add inpatient beds in rural areas, 50 each in rural counties in the state’s three regions, using some new beds and some conversions of existing acute-care beds.

“I want to compliment the General Assembly,” said Christine Craig, vice president of government affairs at WakeMed Health and Hospitals. “They are trying to come up with some creative solution and honor what the Dix money should be spent on. They looked across the state and looked at areas that have unused acute beds.”

The communities in rural areas, including one to be located near Wake County, should get both improved behavioral-health services and increased employment opportunities from the new beds, Craig said.

The North Carolina Hospital Association backs the creation of beds in rural hospitals in principal, said Julie Henry, its vice president of communications.

“We’re supportive of the use of the Dix money for that purpose,” Henry said. “The devil’s in the detail. I think that the idea of making use of some of the beds that exist is appropriate.

“We know that just adding more beds is not the answer,” she said. “The biggest issue we face right now is boarding people with mental illness and substance abuse problems in our emergency departments.”

The Senate plan calls for spending less than half the House’s proposed $25 million, earmarking $12 million in funding to “rural areas of the State with the most limited inpatient behavioral health bed capacity in comparison to their needs.”

In addition, the Senate discusses putting Dix money not only toward psychiatric beds, but also for facility-based crisis centers, like the UNC-staffed WakeBrook center that Wake County funds in Raleigh. These centers care for people in crisis, sometimes negating the need for patients to go to a larger psychiatric hospital. But for the many patients who do need a bed, their options are limited by the shortage of residential beds.

“Our role there is to assess and determine next steps,” Denise Foreman, assistant to the Wake County manager, said of WakeBrook. “But everything is full; the state beds are full, the private beds are full.

“They are supposed to come and leave in 24 hours and they are stuck there for days. We have to close the doors for our assessment center and we have to start diverting people to a hospital.

“If you have a minor infraction, they have to take you to the jail.”

Help for people with mental-health crises in rural areas is also hard to find, leading to the House provision to locate the new beds at hospitals with telepsychiatry capabilities. Telepsychiatry allows patients in areas lacking enough clinicians to deal with a psychiatrist through a remote, secure video connection, with a health professional in the room with the patient.

Telepsychiatry has been widely adopted as a cost-saving measure and has a strong North Carolina center in East Carolina University’s Center for Telepsychiatry and E-Behavioral Health. The associated North Carolina Statewide Telepsychiatry Program provides connections to hospital emergency departments across the state.

Advocates and mental-health professionals have good things to say about telepsychiatry, but also wonder whether its use represents another attempt to address the issue in a piecemeal way.

“We know that telepsychiatry is an innovative way to provide psychiatric services to folks,” said Robin B. Huffman, executive director of the North Carolina Psychiatric Association. “We hope that when these beds are established there will be enough staff to treat these patients.”

Psychiatrists who treat patients via telemedicine should be familiar with the person’s community, so that he or she can make recommendations for local services, Huffman said.

The NC Psychiatric Association hasn’t taken a position on the House versus the Senate plans. In Wake County, the local branch of the National Alliance on Mental Illness says more money should go toward a wider range of care.

“We’ve always thought that [Dix] money was supposed to be earmarked for people who are out of hospitals,” said Gerry Akland, past president of the NAMI Wake County chapter.

“They really need strong support services. We’re strongly advocating for supported housing for people.”

People who qualify for Supplemental Security Income disability payments from Social Security often can’t afford a one-bedroom apartment in a low-income neighborhood, Akland said. But those who can find a place to live can live independently with the help of an ACT, or assertive community team, of mental health professionals, nurses and other specialists.

“If they could have an ACT team to come by once a day, that would certainly keep them out of the hospital,” Akland said.

But that’s only if someone has a place to call home.